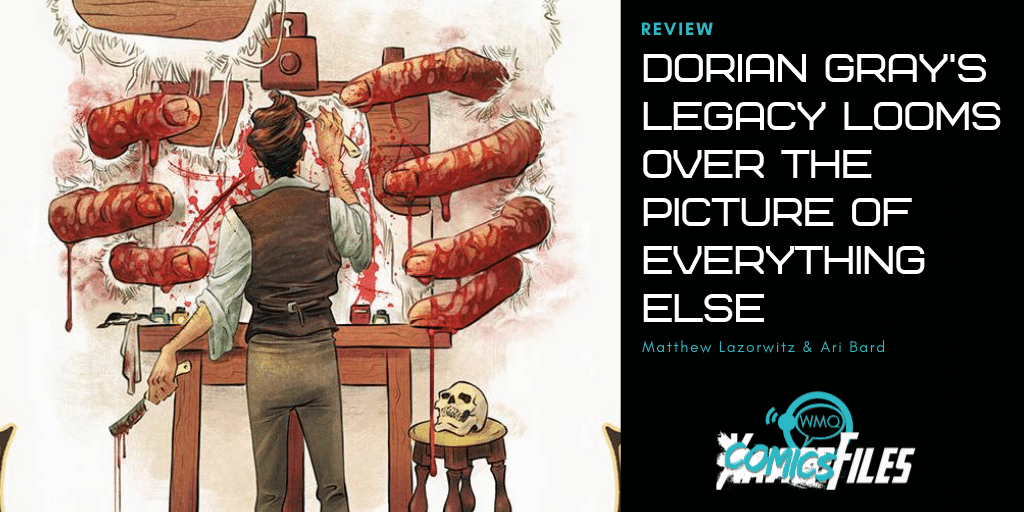

In the waning days of the 19th century, portraiture appears to be on its deathbed. With the arrival of photography, there is much debate over the usefulness of portraits now that a device can capture a person just as they appear. For struggling artists Marcel and Alphonse, the beauty in portraiture can never be replaced, but after they stumble upon the home of Basil Hallward, they learn that true art can not only capture the world, but also change it. It’s Vault Comics’ The Picture of Everything Else #1 by Dan Watters, Kishore Mohan and Aditya Bidikar.

Matt Lazorwitz: I’m an easy mark for the combination of classical literature and modern graphic storytelling, so this book was one I’ve been looking forward to since it was solicited, and I’m excited to get to partner with you to talk about it, Ari.

Ari Bard: Likewise, Matt! While I had not read Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray prior, I am always looking for an excuse to read more of the classics, and comics and other works that take the opportunity to riff on other great stories always fascinate me. I’m excited to dive in!

‘An artist should create beautiful things, but should put nothing of his own life into them.’

ML: There are plenty of places to start, but I think one of the best places would be how this book intersects thematically with Wilde’s original text. Wilde never actually used the phrase “art for art’s sake” in his writing, but it’s come to be associated with him. In the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde wrote, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.” This is something Alphonse, our apprentice monster, seems to have taken to heart. For him, all life, all transgression, is art, and changing life through art is the goal, regardless of its morality, for art has no morality.

AB: That’s true, and it’s a very interesting concept because despite saying that art itself can have no morality, The Picture of Dorian Gray largely wrestles with the nature of whether art can affect one’s morality. We see how a painting, a play and a book affect Dorian Gray’s behavior, and we see how art can move one to action. Our protagonist Marcel, for example, clearly doesn’t like stealing as much as Alphonse does, but will do it for the sake of funding his art. So the danger of art itself having no morality, no responsibility, but being able to change those things in others is the very predicament we are faced with in this first issue. Alphonse comes across Basil Hallward himself concretely changing the world, by killing people, through his art. It is absolutely immoral, but it is nonetheless the power Alphonse strives for, and so while Alphonse claims he will be Basil’s apprentice for the sake of Marcel, I sense there are more sinister ambitions at play, but that is something we may get into later.

ML: Oh, I think you have it there, my friend. Alphonse might need the pretense of saving Marcel as the thing he finally needs to let go of the last of his inhibitions and become the work of art he has always dreamed of being. He actively says to Marcel he will try to subvert Hallward’s evil when he can, but he immediately obeys Hallward’s order. Alphonse’s narcissism is evident long before he encounters Hallward, in how he treats Marcel, and Marcel calls him out on it, and he seems to see nothing wrong with being the center of the universe, which is not a good sign when he can get the power to change the world and the people around him.

AB: You’re definitely right. Watters may throw us right in the middle of things, but Alphonse’s self-indulgent behavior is loud and clear. He’s the louder and more charming smooth-talker, and while we know Marcel sees Alphonse as a close friend (if not something more), Alphonse’s attitude toward Marcel is much more ambiguous. Their relationship is actually something I wish we would have learned just a little bit more about in this issue, and it happens to be our next topic.

‘The only way to get rid of temptation is to yield to it.’

AB: The relationship between Alphonse and Marcel is interesting. There are a lot of parallels here between Lord Henry and Dorian’s relationship or Dorian and Basil’s relationship in the original text. We’ll have to see how things turn out. Nonetheless, the strong queer undertones are equally as apparent here, and I appreciate that. We see a rather onesided enamoration between Marcel and Alphonse, and while both acknowledge the powers of each other’s work, we see that Alphonse comes across as the more worldly artist. Just as in the original text, there’s the sense that even though they saw each other every day and worked side by side, Marcel was chasing someone he could never quite reach.

ML: It’s next to impossible to talk about any work by Oscar Wilde without addressing the queerness of it, and Dorian Gray is possibly his most overtly queer work, even if everything is still heavily coded. Watters absolutely takes those themes and brings them closer to the surface while still dealing with the mores of the time. When Alphonse kisses Marcel, he prefaces the kiss by saying that they are “living transgression.” It’s another of his artistic statements, and it feels like he is taking the affection he knows Marcel has for him and using it to forward his own agenda without actually caring. Marcel addresses it as cruel, and it absolutely is. And the fact that Alphonse’s reaction is to walk off and take a swig from a Champagne bottle is more telling than any words.

AB: Definitely. The phrase “stringing him along” doesn’t even come close to describing the full extent of this one-sided relationship, but it does provide some appropriate imagery for what’s going on throughout the issue. The only time Marcel can get Alphonse to do anything is when he is literally grabbing Alphonse and pulling him to another room or location, but Alphonse appears to have Marcel by a string. We see Alphonse walk around the room at the party with Marcel always close behind. Then, even when they part early in the evening, it’s Marcel who runs back to Alphonse and then follows him to Basil’s home. Even at the very end, it is Alphonse who disappeared and left Paris, but now that he’s back, I suspect it will be Marcel who looks for Alphonse, not the other way around.

ML: And the worst part is that this is something that Alphonse is fully aware of. When Hallward confronts him about letting Marcel go, he asks if Alphonse loves him, and Alphonse’s reply is, “In my way. Perhaps.” His way seems to be as far as he can push someone and use them for his own ends, but it does seem to be the one moment of true contrition that Alphonse feels, at least from his expression on the panel.

AB: There does appear to be some truth there, but I do question how much of a relationship Alphonse feels he really had with Marcel, as he always appears to keep him at arm’s length. Meanwhile, when Alphonse tells Marcel to leave, you can see in his eyes that he feels the two of them being ripped apart, and there’s a lot of emotion in that moment amplified by the horror that it’s not the only thing that can be ripped apart. Isn’t that right, Matt?

‘There were moments when he looked on evil simply as a mode through which he could realize his conception of the beautiful.’

ML: We’ve spent this review talking about this comic mostly as an art piece, or a relationship comic, but if you know Dan Watters’ work, you know he writes a mean horror comic. He’s the guy who wrote a comic where the devil with no memory and his eyes gouged out was trapped in a skull. So it’s not surprising that he breaks a scene midway through with one of the two members of the conversation being literally torn asunder down the middle. It is … a striking visual, to say the least.

AB: It’s extremely effective. I think Watters is quite good at structuring horror on the fringes of whatever other elements he’s utilizing until the perfect moment, and then the full creative team is able to come together for perfect imagery like the scene you just mentioned. We see this in both Home Sick Pilots and The Picture of Everything Else. We hear Basil first mentioned as “The Englishman,” and tales of the Paris Ripper are brought up in conversation before we see anything else. We see blood drip from the torn painting before the splash of Louis being torn in two himself. It appears Basil was able to return and reach Paris after all.

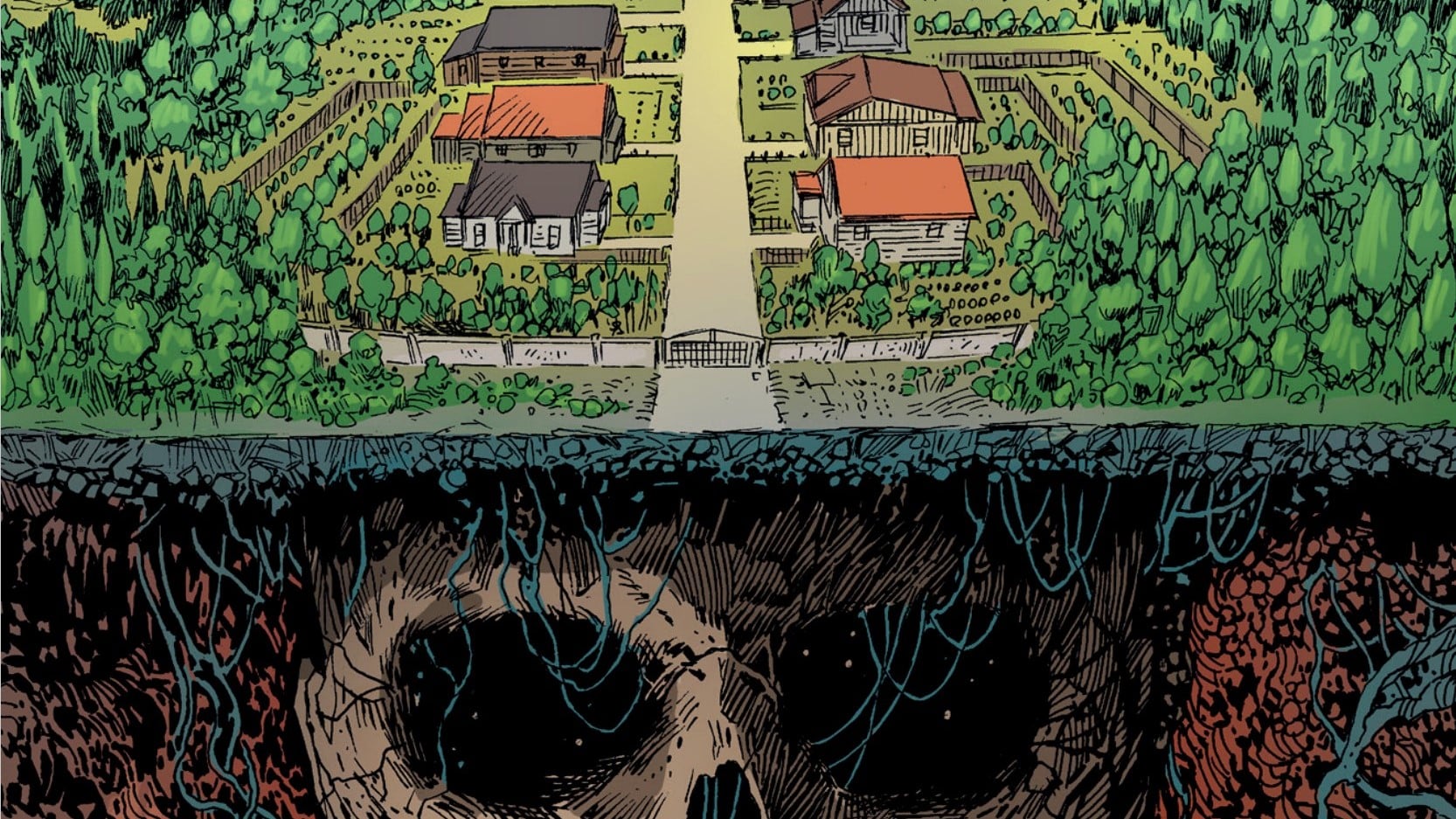

ML: The question of Basil’s resurrection is a big point of curiosity for me. He says very casually that he has returned from the dead before, so it’s not like his fate from the novel changed; it’s just that something happened to him after, to not just bring him back, but to take someone who was a good man and turn him into an unrepentant killer. I’m curious to see what that was, or if it’s going to remain some hinted-at horror, which might make it all the darker.

I’m not an expert when it comes to coloring in comics, but there’s something about the contrast of Kishore Mohan’s soft what-I-believe-are watercolors against the brutality that makes it all the more surreal and horrifying. If that scene of Louis Dupree’s death had been colored like one of Ryan Ottley’s gruesome death scenes from Invincible were colored, it would have felt lurid. But the paint splatter is a great touch. A painting is being torn, and so the blood from the painting drips like human blood and the blood from the human looks like paint. It’s a brilliant artistic touch. And the colors and art are just as sinister and subtle when Alphonse throws the painting of Louis’ twin, Leon, onto a fire, and we cut to see him begin to spontaneously combust. It’s a subtle moment, too, where we could have seen him burn and flail, but instead we cut back to watch the painting burn instead.

AB: I love how the creative team is able to blend reality and art here, as it’s not just the colors. The entire style changes in moments like these. It all starts with Louis’ gruesome death, but art and reality quickly begin to blend more and more. Whether it be the panel of Hallward, swinging at Marcel with his cane, moments when Alphonse has Basil by the throat, or when Alphonse is throwing the paintings into the fire, each of these moments has a more painted, acrylic-like texture. It’s almost as though Alphonse’s actions are causing him to become art. The thing that keeps crossing my mind, however, is that we’ve seen the damage Basil can do with portraits, but it appears Alphonse primarily creates landscapes. The world is his canvas. What horrors will he be capable of?

Miscellany

- For the sake of attribution, the quotes that begin each section of this review are drawn from the original text of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

- For a book inspired by The Picture of Dorian Gray, the name Dorian Gray is not mentioned in this issue. It’s a nice touch.

- If you’ve read The Picture of Dorian Gray or this book and are curious to learn more about Oscar Wilde, you should read or find a production of Moises Kaufman’s play Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde.

- Huysman’s Des Esseintes is a reference to the protagonist of Huysmans’s A Rebours, a novel about an eccentric and isolated aristocrat who retreats from society into art until he is unable to distinguish between the two. It was said that this work was a primary influence for The Picture of Dorian Gray.