Nobody knows why the skyscraper-sized mechs known as ‘Giga’ fought their bitter, centuries’ long war. All they know is that when the fighting finally stopped, the dormant Giga became humanity’s new habitat and new gods in one. When disgraced engineer Evan Calhoun finds an apparently murdered Giga, his society and the fascistic tech-centered religious order that controls it are rapidly thrown into chaos. Zach Rabiroff and Ian Gregory check out the new Vault Comics series by writer Alex Paknadel, artist John Le, colorist Rosh and letterer Aditya Bidikar.

Zach Rabiroff: Welcome, congregation, to the Holy Church of the Enormous Robots. We are gathered here today in the presence of our mechanical overlords to observe the solemn debut of GIGA, the new series from Alex Pakenadel and John Le about a distant yet eerily familiar human society living in the shadow of fallen mech gods. I’ve been enormously excited to read this debut, which might come as a surprise to some of the people who know my reading habits, since I really don’t have much experience in the way of mecha fiction. Sure, I’ve read every issue of the 1980s Doug Moench/Herb Trimpe Shogun Warriors (as who among us hasn’t?), but my encounters with any of the Japanese innovators in this genre are virtually nil, and I could hardly tell a Gundam from an Astro Boy if my voting rights depended on it. Thankfully, I’m joined by my colleague, the Rev. Robowarrior Ian Gregory. And Ian, I take it you’ve got quite a bit more background in this area than I do, isn’t that right?

Ian Gregory: Some would say too much experience, Zach. I co-host a giant robots podcast (Mech Ado About Nothing), and I’ve seen a wide range of mech anime, from the classics to more recent stuff. I’ve really been looking forward to this series, as I’m always interested in seeing how western creators adapt settings and tropes that are most prevalent in anime. There’s been an upswing in kaiju-related comics lately as well, which is something of a sister genre to mecha. What parts of mecha are being preserved here, and what’s being changed? Where are Paknadel and Le going to take us that we haven’t been before? I’m going to constantly be calling back to various mecha series as we read this book, but not for the purpose of comparing quality. Instead, I’m interested in how this series plays with time-honored tropes and innovates on them. The biggest question I always ask when encountering a new mecha series is, “Why are there giant robots in this? Could this story be told without them?” That’s the perspective I’m coming from.

Stop the Machine, I Want to Get Off

ZR: I want to start at the end of this issue, with an epigram from E.M. Forster’s 1909 short story “The Machine Stops”:

The Machine develops – but not on our lines. The Machine proceeds – but not to our goal. We only exist as the blood corpuscles that course through its arteries, and if it could work without us, it would let us die.

Forster’s story (like all of Forster’s stories, really) was a kind of despairing corrective to Edwardian visions of technologically driven social utopia. Early 20th century Europe was something akin to a society of steampunk Silicon Valley tech bros, convinced that industrial development and human ingenuity would negate all the social and economic ills plaguing our benighted past. But for Forster, technology was not a miracle cure, but a deadly addiction. His story was a vision of a future where mankind has become so dependent on its mechanical inventions that it no longer even remembers how to function on its own. His characters, without even trying, have reduced themselves to the status of mere body parts to a mechanical whole. Having invented their gods, they quite by accident became slaves to them.

This is all worth mentioning because I think it helps us to understand what’s going on in the stunning sequence that opens this issue. We’re introduced to our protagonist Evan, 13 years before the main action of the series, as he tours a temple made from the body of a huge, fallen mech with his fellow high-born initiates of the Order of the Red Relay. And let me pause here for a moment to say that I absolutely love John Le’s visual design for the temple complex, with its sunlit hollow eyes resting below stained glass panels, like some kind of high-medieval robot body horror. And I’ll also pause to let you get a word in edgewise, Ian. What did you think of this cold open, and the society it portrays?

IG: I was drawn to two things about this setting made clear in the opening. First, our story takes place after the anime is over. The War of the Giga is over. We won (or so it seems). The Giga aren’t going to get up and go smashing into each other anytime soon, and our focus here is instead on the society built around the mechs. The fatal flaw of most series with giant robots (except for maybe Patlabor) is that they inevitably focus on people using those giant robots, on waging war. These are interesting stories, but they often chart in similar directions, and leave little room for exploring in what ways the very existence of giant robots would change the lives of ordinary people. That Giga isn’t a series about robots fighting may not seem particularly revolutionary, but it does challenge a core assumption of the genre (which is, why would you have giant robots if they aren’t going to do anything?).

The second element stressed here is the worship of the Giga as a religion. Giant robots as god figures, or as gods themselves, is nothing short of an all-time classic mecha trope, from 1972’s Mazinger Z to 1980’s Space Runaway Ideon to 1995’s Neon Genesis Evangelion. Mecha are, in many ways, a greater form of humanity. They are larger and more powerful, capable of being upgraded and repaired. Mankind wages war in mecha because they are a stronger version of us (Why else would we make the mecha in our image?). The inversion of this is not that man made the giant robot in our image, but that we are in the image of the robot (much as God made Adam). Mankind is subject to the whims of the mecha much as we are to the whims of a god. This opening sequence makes clear that, to this church, the Giga are a benevolent god, who shelter and protect mankind. There are implications of danger here, however: What if mankind harms a god? What if we attempt to create our own, new gods? These are questions Giga seems intent on answering, as we see in the later scene of this issue.

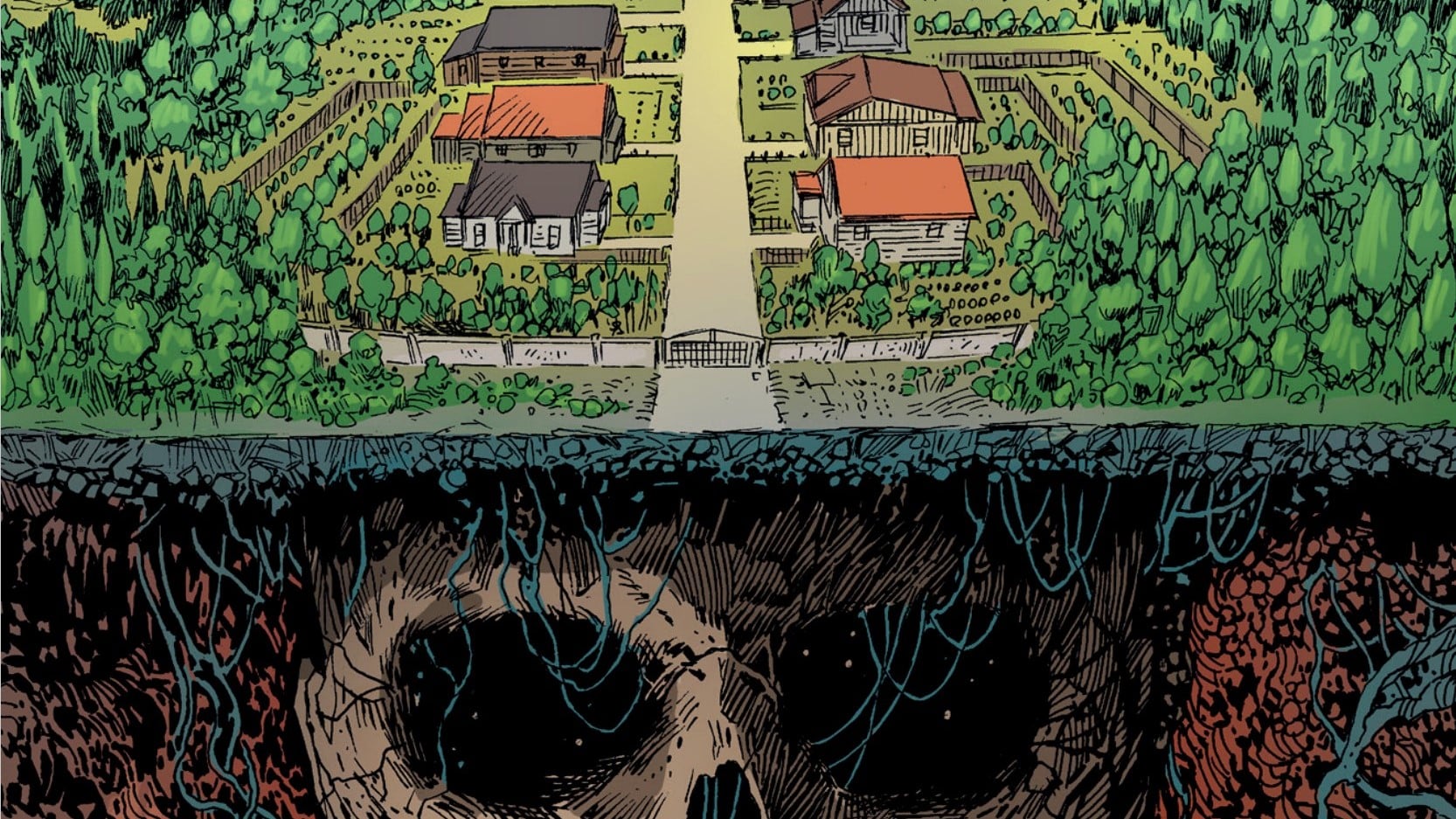

The last thing I want to touch on in this opening scene is on some of the imagery. First, a note on scale. I consider standard mech size to be 18 meters tall – roughly the size of a Gundam. I would argue that’s the most common size (give or take a few meters), and covers maybe 70% of mechs you’re likely to see. The Giga here are operating on a completely different level, and we see them in a sitting, not standing, position. This moves them more into the realm of the super robot, a genre of mecha that dispenses with hard science and realism in favor of massive, over-the-top stakes and action. Super robot is conventionally viewed as more of a children’s genre, but when taken seriously the heightened action gives off a sense of cosmic horror (See: Giant Robo: the Day the Earth Stood Still or the aforementioned Ideon). Lastly, our images of the city call to mind Macross City, which may or may not be an intentional reference (to 1983’s Super Dimension Fortress Macross, better known in the States as the source material for Robotech). Regardless, this sense of scale (and the looming dread of constantly being supervised by sleeping robot gods) heavily reinforces the religious themes.

ZR: So, yes, let’s talk a bit about those robot gods, and the war they waged. While the nature of the mech genre is, as you note, people using robots as extensions of themselves, this setup actually tweaks that formula in another important way: The implication in our introductory paragraph is that this wasn’t a war of man-against-robot or man-piloting-robot, but of the robots against one another. And the reason and logic behind that battle remains a mystery to the humans left in its wake, which is why they’ve constructed a whole faith seeking to understand it. The terms Evan uses to describe their objects of worship are particularly intriguing: “The gods built the Giga to fight their battles for them, right? They were never meant to survive on their own.” If the Giga are gods to man, who are these gods to the Giga? The looming specter of Forster’s story suggests it might be mankind itself – but, if so, it’s a stage of development that post-war humanity no longer remembers enough to comprehend.

I think it’s significant that when Evan proffers his theory about man’s purpose to the Giga – that we serve the function, in the Monseigneur’s words, of “keep[ing] them regular,” – the priest bitterly dismisses his position (which, as the rest of the story makes clear, is surely the correct one). Like any religion, the Order of the Red Relay long to see themselves and their species as central to their world and privileged among the gods even against all empirical evidence. But in order to maintain that privileged position, they’ve created a stratified and wildly unequal society, rooted in hereditary caste, and implicitly intolerant of both dissent and physical imperfection: the Monseigneur’s sneering remark that the wheelchair-using Evan is “half-initiated at that,” is surely meant as a dig at more than his clerical status. It’s not so much an exaggeration of our own society as a logical leap from it. If inequality and authoritarianism are endemic to human society, how might they manifest in a post-apocalyptic mecha world? Probably an awful lot like this.

IG: And to jump in here, Evan being disabled also profoundly affects the mech metaphor. If the mech is an extension of the human form, it is also a kind of radical prosthetic. Various series have played with this idea before (Gundams Thunderbolt and Iron Blooded Orphans, for example) but never with a great deal of tact. This is an additional complication on one of the genre’s core assumptions, one which I hope is fully developed.

ZR: And then, at the other end of all this (and appearing a bit later on in this narrative, but let’s go wild and jump ahead a decade or so) are the Dusters, the “luddite” militants dedicated to the overthrow and destruction of the Giga and all that they represent. I found our brief glimpses of this faction absolutely fascinating, from their taboo refusal to set foot inside Giga bodies, to their bizarre, pseudo-robotic battle wear. It seems, at least by my reading, that the clothes serve a purely practical function on one hand, letting the Dusters approximate the effectiveness of a Giga in combat. But at the same time, it evokes what an anthropologist might call sympathetic magic, evoking (and co-opting) the spiritual power of the Giga by making an ersatz impression of their appearance. The Dusters are a bit like the Pacific Cargo Cults of World War II, who created formalized impressions of landing strips and military equipment out of wood in order to summon the technological power that had once been in their land. The Dusters may be aggressive protest atheists – the Richard Dawkins to the Red Relay’s Church of England – but they respect the power of their enemies. What did you make of this second faction, Ian?

IG: I’m interested in the source of their distrust of the Giga. It’s a somewhat natural progression for the Order — of course a religion would spring up around the life-giving giant robots, but where did the Dusters first develop? What led them to distrust the Giga and reject the safety they offer? I think it would be easy for Paknadel to take the extra step and depict the Dusters as a shamanistic alternative to the Order, living as one with the land, etc., etc. Instead, they seem eminently sensible, suspicious of what seem to be a splinter-sect led by a (dismissively called) guru. There’s also an obvious prejudice against the Dusters, too, even for the ex-Order Evan (“I still have my kidneys”), so their image seems to be that of barbarians, despite the fact that their technology hardly seems outdated compared to what we see in the big city. This is a world where the greatest cultural distinctions are drawn based on where you live. Evan’s apartment in the foot of Giga is considered low-class, so the huts and encampments of the Dusters must be seen as particularly barbaric. I wonder, then, if the finer elements of society (the priests, the law enforcement) live in things like the head (and therefore, cockpits?) of the Giga. Evan’s cop friend (?) Mason makes a reference to Aiko as “low-born,” which he and Evan are not. Is “low-born” literal? Literally, born lower on a Giga?

ZR: I love the idea of a literal meaning to the terms low- and high-born, which would also set up a great metaphor at the close of this issue when Evan and Laurel scale the enormous Giga shell, symbolically elevating themselves above high-born society itself. If that hasn’t been a part of Mr. Paknadel’s plan from the beginning, he should feel free to take this idea for the very reasonable Xavier Files consulting fee of $5.99 (sales tax where applicable).

And you’re of course right to draw attention to the fact that there isn’t exactly a moral equivalence between the two sides in this human war. The Dusters, for all their violence and doctrinaire practices, are opponents of what is quite visibly an authoritarian theocracy. The series is admittedly running a risk here of falling into the trap of an extremists-on-both-sides metaphor, but for now, at least, I think the story ably avoids it. That’s partly because the world-building is convincing enough that it never feels like it’s trying to echo contemporary politics in a one-to-one way: these factions are imaginative extensions of human nature, not analogues for any single religion or political ideology. And partly it’s because Evan and Laurel are set up as outcasts and rebels in their own right. They aren’t comfortable moderates clucking their tongues (or speakers) at the Bad People on Both Sides, they’re opponents of active or potential oppressors on two sides of a war. It’s a whole lot easier to sympathize with proponents of the middle path when that path seems so dangerous, oppressed and opposed to the powers that be.

I Stan Laurel

ZR: Beyond the heady philosophical themes, the heart of the story, once Paknadel gets into the present-day narrative, is the friendship between Evan and his Giga friend Laurel. By giving up his place in society to help save Laurel, Evan is of course living out the religion he espoused in the opening scene: he’s acting as a microbe healing and preserving a superior being. And yet, little, childlike Laurel doesn’t seem all that godlike or superior up close. They’re more like a wild animal captured out of his natural habitat before they could learn to survive: they’ve lost whatever instinctive capabilities they might have had, and what’s left is a poignant (and frankly adorable) vulnerability. They don’t even remember seeing their own species before, the poor robo-kid!

That dynamic puts an interesting spin on the Forster epigram. Humans may have lost the ability to live except in the shadow of machines, but machines (or this machine, anyway) have likewise lost the ability to function except with the aid of humans. Their relationship is truly symbiotic, not oppressive (as the Dusters would have it) or privileged (as per the Order of the Red Relay). So Evan’s choice to stake out a middle path feels right, necessary and dangerous all at the same time.

It’s also an inspired move to place a non-human character squarely at the center of this book alongside Evan. It not only focuses the broad sci-fi world building through the lens of a single friendship, but it gives the two lead characters a cute, Odd Couple dynamic that adds a surprising amount of humor to what might otherwise be a pretty grizzly setup. I don’t know about you, but I thought it worked beautifully.

IG: First, a bit of nitpicking. Laurel’s existence raises the question of whether the Giga were ever piloted to begin with. I’ve been operating under the assumption that they were, as that would make them mechs, but if Giga are actually fully-functional AIs, then they would actually be giant robots and not mechs. This does not really matter, except to me.

Symbiotic seems to be the right word, and one that supports Evan’s hypothesis in the intro sequence. A central question to me seems to be the purpose for the Giga; will imbuing Laurel with a better processor change them in a fundamental way? Will it cause them to revert to their initial purpose? Laurel already can’t control their strength, as seen by the dead squirrel, and unleashing a Giga, no matter how small, on a sleeping world may have disastrous consequences. Evan and Laurel support each other, but his modifications stray dangerously close to Frankenstein territory, and are predicated on the good will of a being he has no real conception of. That “thinking brains” like Laurel are outlawed, even by the Giga-worshipping Order, suggests a kind of dark truth to the Giga, such that their reawakening could possibly be disastrous. The Giga were created to solve some kind of problem; what would they do if they were to return now, with no target? The giant robot as double-edged sword trope is a classic one, and I couldn’t help but feel unease when Laurel was on the page.

The power of this setting, so far, has been the sheer number of questions it has raised. I’m hungry for more information about the Order, the Dusters, the Giga, Evan’s past, Aiko and all the mysteries raised so far in the series. There’s a lot of potential in this setting, and a lot of different angles to be explored.

ZR: The understated menace in the sequence around the dead squirrel might actually be the most chilling moment of the comic. It’s a subtle reminder of the physical threat that even the smallest of Giga can pose. After all, these robots clearly did a number on human society at some point in the past, even if the cause and motivation behind that destruction remains opaque. These are living creatures with sentience and humanity, but they are also, for all intents and purposes, walking atom bombs. And those bombs have exploded at least once in human history. Is it really worth taking the risk again? Laurel is cute and friendly so long as they abide by the ethical standards of human society. But can those standards really be inculcated into such an utterly different synthetic species? Should they be? Or is that just imposing our own codes of action onto a wild species that has moved beyond them? These are thorny questions, and it’s going to be fascinating to watch this series grapple with them over time.

The violent potential of sweet, little Laurel also highlights the physical contrast between the Giga and Evan. And it’s worth bringing up the obvious fact here that the story’s hero is in a wheelchair. It’s a fact I almost didn’t think to mention, for the simple reason that it’s handled with such a consistently light touch that the story never explicitly draws attention to it. But it’s an ever-present fact of life for him, and while his condition is never belabored, it nevertheless poses a clear point of physical challenge and danger, as during the fraught sequence when he and Laurel scale the Giga shell near the story’s end. Even in 2020, that kind of visible representation of disabled protagonists remains exceedingly rare in comics (or, indeed, any media), and to see it handled here with sympathy, humanity and dignity honestly warms my heart.

One additional point while we’re on the subject of representation. The human world that Paknadel and Le depict here appears to be broadly multiethnic, and that diversity extends to Evan himself, who is Black. It is, of course, tremendously important to see a hero of color placed front and center of this story, and all the more so in this of all years. Interestingly, unlike disability, there doesn’t seem to be any ingrained prejudice toward skin color in this sci-fi world (at least based on our glimpses this issue): The Order of the Red Relay is segregated along any number of lines, but race doesn’t appear to be one of them. Give one point to apocalyptic robot destruction, I guess.

What Do You Mecha All This

ZR: So let’s talk a little about the storytelling itself, both in words and pictures. I’m tremendously impressed by the structure of this book, which manages to pack a whole lot of world building and dramatic mystery into its first seven pages alone, before we even get to the present-day setting. And yet it never once felt to me like we were being weighed down by excessive exposition or plotless table-setting – the bane of most modern first issues, which struggle to fit a semblance of a plot alongside necessary setup. That’s a result of the nimble script from Paknadel, who has really emerged in a few short years as one of the most natural and capable dialogue writers coming onto the comic scene. Just look at how much information he embeds in the short conversation between Evan and Mason — the two characters’ shared childhood, the existence of the nomad Giga, Mason’s knowledge of the secret behind Aiko’s death – all while setting up the fraught relationship between these two men. You wouldn’t even think about it unless you parsed out what each line of dialogue was doing, and that’s the mark of a skillful writer: He makes it look easy.

And I absolutely dig Le’s linework, which is exaggerated and distorted, but never veers so far into the realm of cartooning that it loses a sense of gritty realism. There’s something wonderfully bizarre about the way he imagines the extremely familiar (shantytowns, cathedrals, articles of clothing) made strange and exotic by the presence of these enormous robots being used in every aspect of life and looming over every setting. But he’s also a clear enough storyteller never to allow the weirdness to get in the way of the action we’re supposed to follow: It was a wise choice to mostly adhere to a grid structure, both because it guides us through the book effectively and because it has the visual effect of repeatedly cutting off the upper extremities of the massive Giga at the panel edges, which only makes them feel bigger. And just to spread the deserved praise around, a few words in favor of the flat, deliberately limited color choices by Rosh, which contrast the grays of fading towns with the red tones of explosions and sunsets. The whole story seems to take place at dusk: appropriate for what feels like fading society. Or is it a new dawn?

IG: This is a 24-page comic but it feels like 40 pages of content. So much information about the world and our characters and the plot is packed into these pages, yet it still feels completely brisk and effortless. First issues are really tricky, and I think there’s a temptation to make them longer, to spend more time introducing characters or the world. This issue wisely holds back a lot of things, half-referenced or unexplained, without feeling confusing or overwhelming. That’s probably the most difficult tightrope to walk, but Giga does it without any problems.

I loved Evan’s character, particularly the way he holds everyone at arm’s distance — even Laurel, to whom he acts more like a patient father than a friend. The dialogue is perfectly natural, another difficulty when introducing a setting, and there’s no awkward “As you know Bob”-type dialogue. Le’s linework is obviously outstanding, but his layouts are just as impressive. The pages are tight, crammed with dialogue, but still show incredible detailing and pacing, like when Laurel’s oil (?) drips onto Mason’s shoulder. There’s a wonderful understanding of how we read comics on these pages, and Le knows just when to pull out or dive in.

I’m glad you called out Rosh’s coloring, as well. The book’s colors are flat, but they give everything a wonderful feeling of texture. It’s rare to read a comic and know instinctively how these things feel, but that sense is captured really well. There’s a lot of red in this book, but also deep greens and blues, often on the same page (I’m thinking of the first page of the Duster Encampment). It creates a strong contrast between the mechanical Giga and the overgrown trees and fields that characterize the world. This is a vibrant book with a clear visual identity. I recommend just flipping through the pages and watching the way the overall color of the pages change; there’s no monotony here.

ZR: I won’t be coy: this is the best debut issue I’ve read this year, and the most promising start to an ongoing series I’ve encountered in quite some time. Paknadel and Le have done something more than write a strong first issue: They’ve created a story rich with ideas, driven by heartfelt sympathy for their characters and mysterious enough to be worth exploring for some time to come. I couldn’t be more stoked to follow these creators wherever they’re headed.

IG: I completely agree. Giga is a supremely technical book, lush with details and hints at a future story. In some ways, I am most impressed by its efficiency, and the sheer volume of ideas, characters and settings it introduces in such a short time. It also perfectly strikes that difficult balance in science fiction: a new and exciting world, full of mystery, that is also inhabited by human characters we instantly relate to and understand. There’s a lot that fans of mecha will recognize here, but there’s also no obvious hints about where this story is going and how it will play out. It feels recognizable and fresh, all at once.